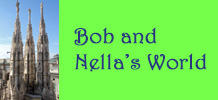

Layout of Castle and Surroundings (1895)

The largest point of interest in Milan would have to be the

Sforza Castle (or Castello Sforzesco),

a fortification that evolved into an approximation of its present-day form in the latter half of the 15th

Century. The castle is enclosed by curtain walls, with towers at the corners, and is square in shape.

Each side of the square is more than 600 feet in length, creating a very large protected area (think 8

football fields, with room to spare). Surrounding the walls there is a moat (now empty), and inside the

walls are several structures, some incorporated into the walls, between which there are three main open

areas: the Courtyard of Arms (Piazza d'Armi, #6 in the drawing above), the Ducal Court

(Corte Ducale, #11) and the Cortile della Rocchetta ("Courtyard of the Small Fortress",

#12). In the middle of the wall that faces southeast, toward the center of town, is the tallest point

of the castle, a 230-foot tower called the Torre del Filarete (#1).

Piazza d'Armi with Carmine Tower

Corte Ducale

Cortile della Rocchetta

Torre del Filarete

While all of this stonework and brickwork appears to be in very good condition for

structures built in the time of Leonardo, it must be admitted that most of what is seen

by a modern visitor was built considerably later than the Renaissance. A brief history

is in order.

Defensive construction in the area of the castle actually began well before Leonardo,

and before the reign of anybody with the Sforza name. Around 1360, the Lord of western

Milan, Galeazzo Visconti II, decided the medieval wall surrounding the city was

insufficient for the city's defensive needs, and that a more functional defensive

structure was needed.

Galeazzo Visconti II

Construction began on a castle which was completed in 1370. The castle was incorporated

into a section of the wall, and it was called the Castello di Porta Giova, being

named after a gate in the wall which it subsumed. At the time, the castle occupied a

rectangular area now corresponding to the Corte Ducale and the Cortile della

Rocchetta, with surrounding structures, and the city wall passed through what is now

the boundary with the Piazza d'Armi. Succeeding Viscontis enlarged the area by adding a

barracks inside the wall and eventually connecting it with the castle. Also, the castle

eventually became the main residence of the Viscontis.

In 1447, Filippo Maria Visconti died without a male heir, throwing Milan into turmoil.

Despite a number of claimants to the Ducal succession, a government called the Golden

Ambrosian Republic was formed, which bestowed previously unknown rights upon the

populace. The castle was seen as a symbol of the Viscontis, who had been rather

despotic, and the structure was essentially destroyed (only some of the foundation remains

today). Unfortunately for the Republic, all of this happened at a time when Milan was at

war with Venice, and one of the Ducal claimants, Francesco Sforza (who happened to be

married to Filippo Maria's illegitimate daughter, Bianca Maria Visconti), also happened to

be a great general, and he was enlisted to repel the Venetians.

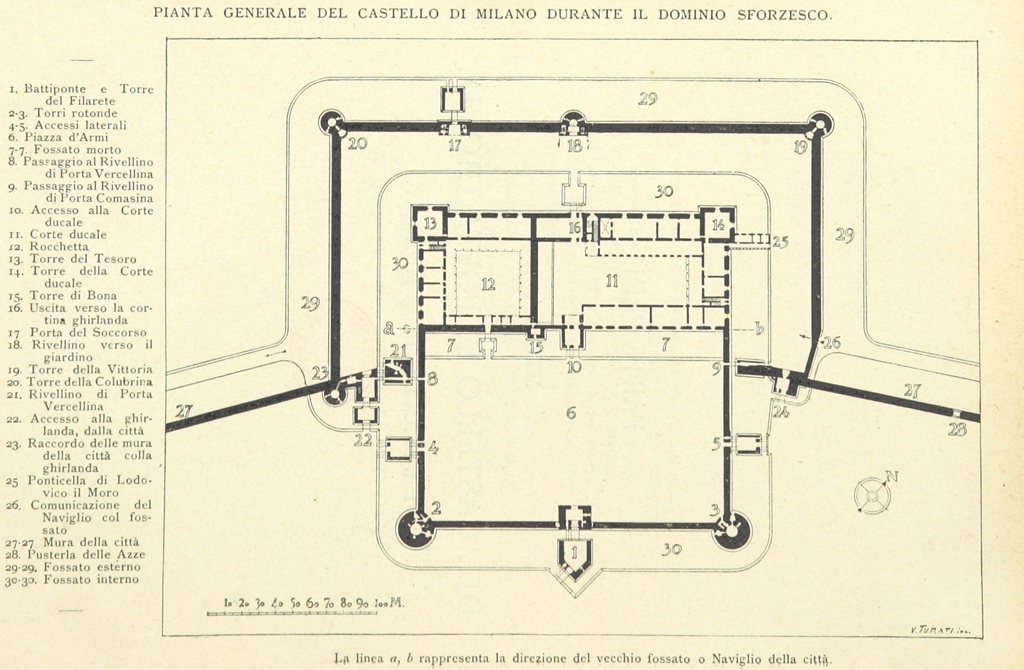

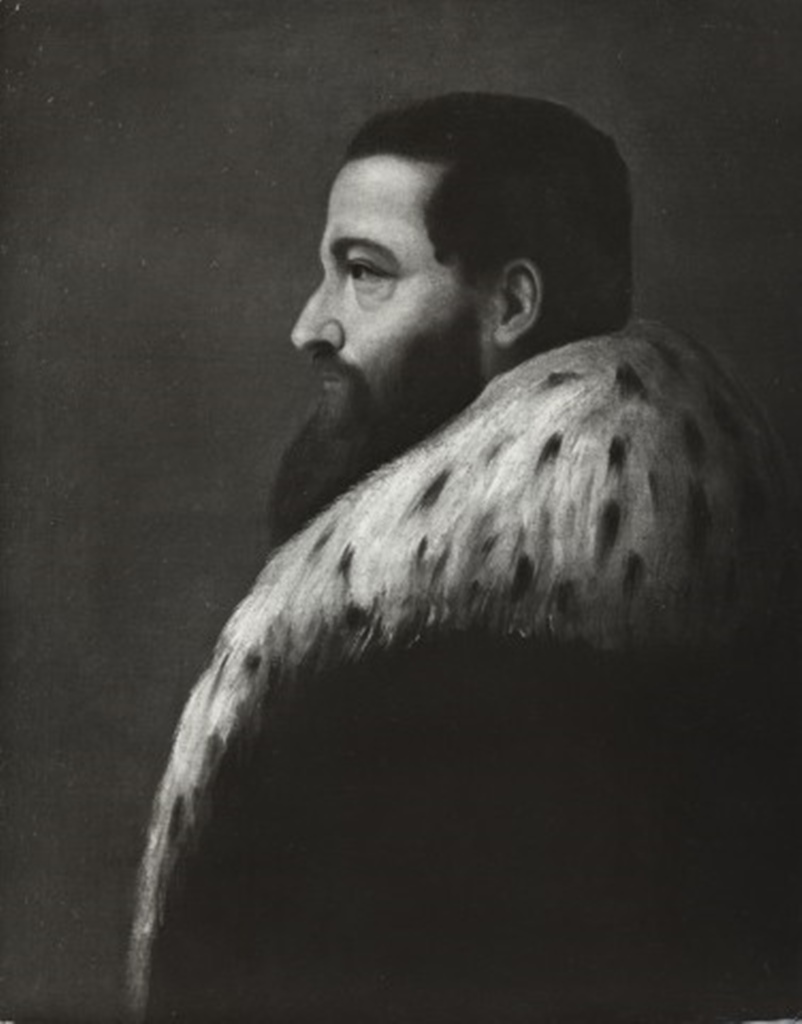

Francesco Sforza

Francesco had great success on the battlefield, but in the meantime there were elements

within the Republic that were plotting against him, as they feared his power.

Francesco found out about this and things got complicated. A series of betrayals

ensued, plus a siege, but in the end Venice was repelled, the Republic was ended, and

in 1450 Francesco Sforza became the new Duke of Milan.

Francesco immediately began the rebuilding of the castle (not a thrilling development

for the citizenry), citing defense and beautification as his reasons. He mainly

employed military engineers for the effort, but he also brought in a civil engineer

from Florence by the name of Antonio Averulino, who was also known as il Filarete.

Filarete was to work on several Milanese projects over a period of 15 years, but his

principal contribution to the castle was the design of the main tower facing the city,

which came to be called the Torre del Filarete. Construction and renovation of

the castle continued under Francesco's successor, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, who moved into

the castle along with his wife, Bona of Savoy.

Galeazzo Maria Sforza

Bona of Savoy

Under Galeazzo, the castle mostly took on the form seen today. But its defenses

were not sufficient for Galeazzo, as he was assassinated in 1476. His son, Gian

Galeazzo Sforza, became the next Duke, but he was too young to rule, so Bona

became regent on his behalf. The ambitions of other Sforzas to rule apparently

caused Bona to feel insecure (for good reason, as it turned out), so she had the

defenses of the Rocchetta portion of the castle strengthened, and had a central

tower built, from which the entire castle could be viewed.

Bona of Savoy's Tower

But again, the defenses were not sufficient, as Bona's brother-in-law, Ludovico, was able

to take advantage of a rift between Bona and her top advisor to force her out in 1481,

at which time he assumed the regency.

Ludovico Sforza

In 1494, Gian Galeazzo, who had been kept prisoner at the Sforza summer palace, died

under suspicious circumstances, and Ludovico became the new Duke of Milan. Ludovico,

known as il Moro, was clearly Machiavellian before Machiavelli, but he was also

quite fond of the arts. Even as regent he brought in architects and artists such as

Donato Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci and assigned them a succession of projects, many

of which were directed at the beautification of the castle.

Donato Bramante

Leonardo da Vinci

But Ludovico's beautification projects were put to an end by the French, who invaded

Milan in 1499. Over the next 30 years, the French and the Sforzas fought over Milan,

with control going back and forth. In 1521, during a period in which the French were

using the Filarete Tower for weapons storage, there was an explosion which destroyed

the tower. Eventually the Sforza line came to an end, with its last ruler, Francesco

II, bequeathing the Duchy of Milan to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor.

Francesco Sforza II

Charles V

You might be thinking of the Holy Roman Empire as being ruled by Habsburgs, who were

Austrian. But, if you've been reading these pages, you may also remember that Charles

was the grandson of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain (through his mother), in addition

to being a Habsburg (through his father). Charles decided to place Milan under the

control of Spaniards, who repurposed the royal residential structures for practical

uses needed for a large military garrison. This began a long period of decay for the

castle, which was not well maintained. In 1706, during the War of the Spanish

Succession, Eugene of Savoy captured Milan on behalf of the Holy Roman Empire. The

castle occupants changed from Spaniards to Austrians, but the lack of maintenance

continued. By 1796, the castle was again under French control, in the person of

Napoleon Bonaparte, who also used the castle as a barracks. Following the defeat of

Napoleon in 1815, Austrians returned, but they were removed following a Milanese

uprising, finally leaving in 1859. This left Milan under the control of Milan.

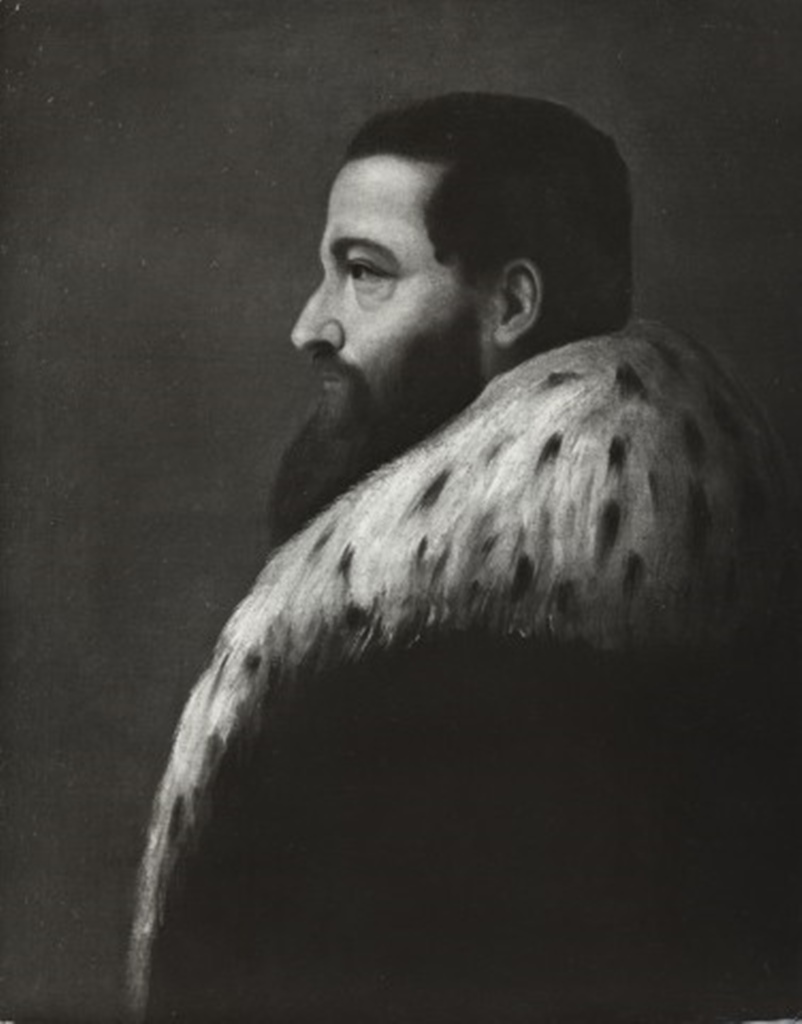

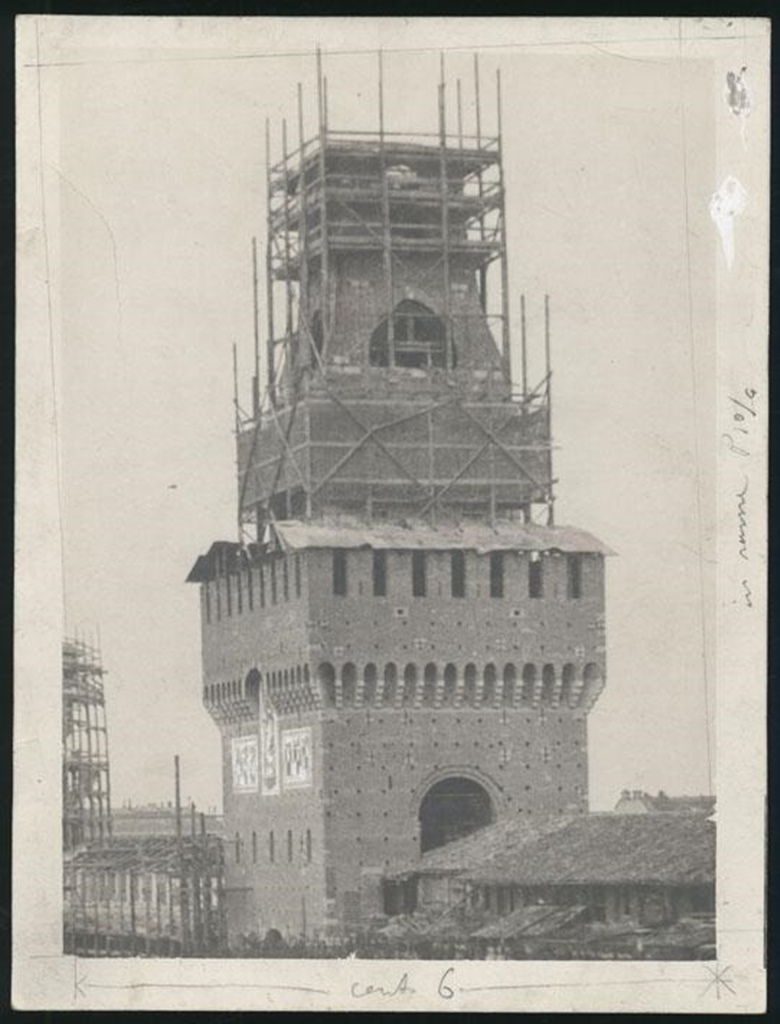

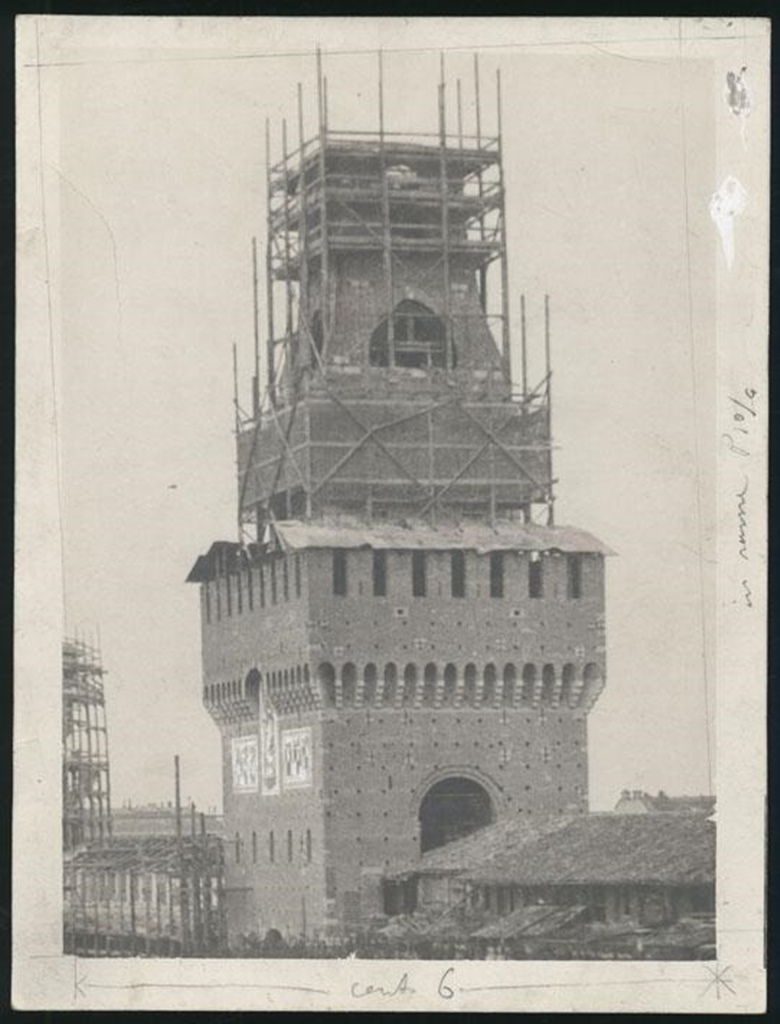

By this time the castle was in pretty bad condition. There was a great deal of

discussion about what should be done with it, and eventually it was decided that the

castle should be returned to its original form, in particular the form it had during

the days of the Sforzas. This would involve the removal of structures that had been

added, rehabilitation of structures that remained, and replacement of structures

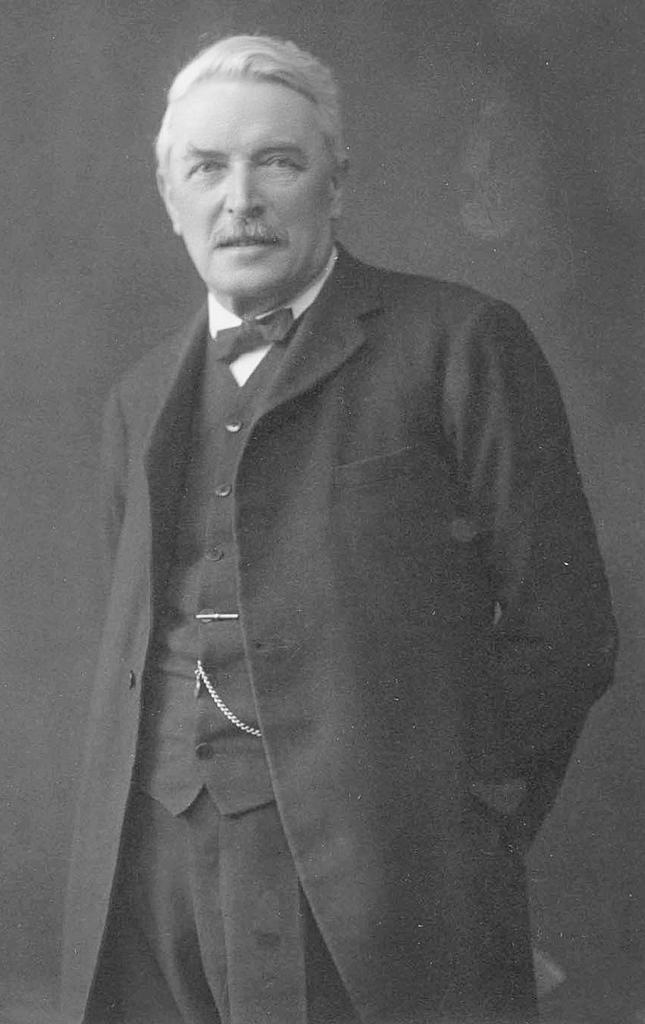

that had been removed. Work began in 1893 under the direction of Luca Beltrami, and

was funded by the population through participation in a public subscription. One

particular challenge was the recreating of the Filarete Tower, which had to be

redesigned based on a careful study of paintings and drawings made before its 1521

destruction. Beltrami also added some details of his own, including a clock, a

statue of St. Ambrose (the patron saint of the city), coats of arms of the Sforza

rulers and a bas-relief of the recently assassinated king Umberto I on horseback.

It was also decided to fill the restored structures with museums.

Luca Beltrami

Torre Filarete Being Rebuilt (1904)

One area of renovation, which we weren't able to see, was a room called the

Sala delle Asse (stop snickering; it means "room of the wooden planks", as the

walls are covered with them). The upper walls and ceiling of this room are covered

with a representation of mulberry trees and a canopy of branches and leaves.

The painting was much deteriorated, and Beltrami's team largely renovated the tree

depictions by painting over them in more vivid colors. It has since been decided (by

a team in the 1950s) that this room is largely the work of Leonardo da Vinci, and an

effort has been underway since 2012 to stop the deterioration and to closely examine

the layers of paint using a variety of high-tech methods. The analysis has helped in

decisions being made as to optimal restoration measures to be taken.

Sala delle Asse (2016)

Despite the Sforza Castle being virtually across the street from our hotel, we did

not start our day by going there. Instead, we walked in the opposite direction,

toward the cathedral, to visit the Ambrosiana Gallery (or Pinacoteca) first.

The Pinacoteca is affiliated and co-located with the Ambrosiana Library (or

Biblioteca), founded by Cardinal Federico Borromeo in 1609. The library has

an impressive collection of books and manuscripts, including Leonardo da Vinci's

Codex Atlanticus, some of which was on display (the full codex is a

twelve-volume set of writings and drawings). The Pinacoteca displays many works of

art from Borromeo's collection (plus later donations), mostly by artists of the

Italian persuasion (Botticelli, Titian, Caravaggio, etc., and even a da Vinci

painting). Unfortunately, the Pinacoteca had a no-photography rule, but here's a

photo of the entrance:

Ambrosiana Gallery

After a break for lunch, we headed for the castle. On the way, we passed through a

small square called Largo Cairoli, in which there was a statue of Giuseppe

Garibaldi and some temporary-looking modern white structures which turned out to be

an information center for Expo 2015, which would be taking place in Milan the

following year.

Statue of Giuseppe Garibaldi

Expo Gate (for Expo 2015)

On approaching the castle, we found some construction work going on, probably an

effort to make the castle look its best for the Expo.

Nella and Filarete Tower

Castle Wall and Carmine Tower

We entered the castle under the Filarete Tower and headed for the entrance to the

museums (the castle is crammed full of museums, which seem to be connected to each

other; it wasn't always clear to us where one ended and another one started), near

the Bona of Savoy Tower. The entrance first took us into the Museum of Ancient Art

(Museo d'Arte Antica). This museum appeared to display artistic objects

from about the 14th Century and later.

Bernabò Visconti Monument, Campione (ca. 1360-85)

Blessed Redeemer (ca. 1350)

Window Decoration

Tapestry - The Sacrifice of Elias and the Prophets of Baal

Madonna and Child, Iacopino da Tradate(?) (15th C.)

Ceiling Fresco

Pietà, Gasparo Cairano, (15th C.)

Painted Stained Glass Window, Lombard (17th C.)

Annunciation Tiles, School of Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (15th C.)

Tomb of the Poet Lancino Curzio, Agostino Busti (1513)

Rack of Swords

Suit of Armor

Statue of Goddess

At the end of the Museum of Ancient Art, there was a statue off in an alcove by

itself which might be the museum's most important possession. This is the Rondanini

Pietà, the last sculpture to be worked on by Michelangelo Buonarroti. While it's

obviously unfinished, its historical importance is undeniable. Michelangelo is thought

to have started work on the statue around 1552, and to have tinkered with it until

shortly before his death in 1564, at the age of 88. There are some accounts that he

went through three versions of the statue, discarding versions that he found

unsatisfactory and ending up with this one. Shortly after Michelangelo's death the

statue disappeared, and all that was known about it were some references in writings

about Michelangelo. In 1807 it resurfaced in the possession of the Marquis Giuseppe

Rondanini, whose family had been keeping the statue in their Palazzo Rondanini in Rome

for many years. At the time, there was skepticism that the statue was the work of

Michelangelo, and it stayed in the Palazzo until it was put up for sale in 1949. By

this time the authenticity of the sculpture had been verified, and it was eventually

sold to the City of Milan in 1952, who put it on display in the Sforza Castle. In

1915, after we'd visited, the statue was moved to a section of the castle which had

been the Old Spanish Hospital. This part of the castle was made into a museum of its

own, dedicated to the statue and called the Museo Pietà Rondanini.

Rondanini Pietà, Michelangelo (1552-64)

After paying our respects to the Pietà, we continued into the next museum, dedicated

to the decorative arts (the Museo delle Arti Decorative). This museum was reached

via a walkway through a semi-sheltered area called the Cortile della Fontana. As

you might expect, in the museum there was an interesting selection of decorative objects.

Bob in Cortile della Fontana

Strongbox, Northern Italy (15th C.)

Ceiling Fresco

Creation of the Plant World, Convent of St. Anthony (ca. 1500)

Madonna and Child, G. Zabellana and L. da Verona (1499)

Pietà, Giovan Angelo and Tiburzio del Maino (ca. 1520)

God with Orb

Lazarus' Resurrection, Flemish (1515-20)

Madonna and Child (15th C.)

Tapestry

Tapestry

Adoration of the Shepherds, Fratelli de Donati (15th C.)

Miracle of St. Dominic, Fratelli de Donati (1495-1500)

A section of the Decorative Arts Museum was devoted to furniture and wooden sculptures,

and had its own name (Museo dei Mobili e delle Sculture Lignee):

Cabinet, Genoa (ca. 1710)

Cabinet Detail

Casket (17th C.)

Hunting Horn, Italian (16th C.)

Cabinet, Genoa (ca. 1579-1629)

Winter Landscape, Theobald Michau (ca. 1700)

Console Table, Genoa (ca. 1690)

Armchair, Rome (ca. 1700-50)

Two-Section Furniture Unit (19th C.)

Dinner Service, Eugenio Bellosio (ca. 1887)

Medusa Dish, Eugenio Bellosio (1884)

Bust of a Young Woman, G. Ponti and R. Ginori (1922)

Leading off from the decorative arts museum was another museum, the castle's

Pinacoteca, which appeared to feature paintings. We didn't get a good look

at exactly which paintings, as the Pinacoteca was roped off from visitors for

some reason. We could see a little of it from the furniture area, though.

Entrance to Pinacoteca (closed)

Leaving the museum, we spent a little bit of time wandering around the castle.

Bona of Savoy's Tower and Cortile della Rocchetta

But eventually, we became tired and returned to our hotel. After resting for a while

and getting dinner, we watched some Italian TV and went to bed. Again, we had

ambitious plans for the next day. They would start with a visit to a museum named

after Leonardo da Vinci.